By Samuel Benin, Senior Research & acting director of the Africa Regional Office at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

By Samuel Benin, Senior Research & acting director of the Africa Regional Office at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

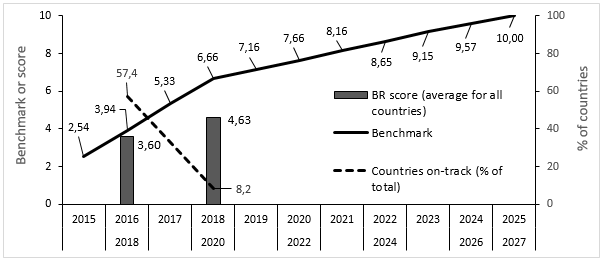

African leaders have remained committed to mutual accountability for actions and results in efforts to transform Africa’s agriculture sector. Since signing the Malabo Declaration on “Accelerated Africa Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods” in 2014, they have released two biennial review (BR) reports and the Africa Agricultural Transformation Scorecard (AATS) that track progress in implementing the Declaration. The inaugural BR report, released at the African Union (AU) Summit in January 2018, showed that 20 or 57% of the 47 reporting countries were on-track to achieve the goals and targets of the Malabo Declaration by 2025. The second BR report, released at the AU Summit in February 2020, shows that only 4 countries (Ghana, Mali, Morocco, and Rwanda) or eight percent of the 49 reporting countries are on-track. Africa overall was not-on-track in both BRs, with scores of 3.60 and 4.63 below the respective benchmarks of 3.94 and 6.66 in the 2018 and 2020 reports (Figure 1). These results indicate a slowdown of progress in implementing the Malabo Declaration.

Figure 1: The CAADP BR benchmarks and results of the 2018 and 2020 reports

Sources: Author’s illustration based on the BR reports (AUC 2018, 2020).

Notes: For the horizontal axis, the years at the bottom are the years that the BR reports are released or expected to be released at the AU Summit, whereas those on top are the corresponding latest years that the data are measured, starting from the baseline year of 2015.

The next BR report is expected to be released at the AU Summit in 2022, using data measured from 2015 to 2020 (see Figure 1). With the COVID-19 global pandemic and the related economic downturn already underway in 2020 and predicted to be particularly bad for Africa (see e.g., Vos et al. 2020), many of the BR indicators measured in 2020 may see big changes for the worse. This is particularly likely for the indicators on policy actions (e.g., investment, trade, and immigration), behavior of actors in the agrifood system (e.g., labor supply and input use), and intermediate outcomes (e.g., food production, prices, and security) that may be more affected by the COVID-19 lockdown. The impact on these indicators will be transmitted to other outcomes (e.g., poverty and nutrition) in later years. Therefore, this may deepen the slowdown observed in the 2020 BR and could persist into the 2024 and 2026 BRs.

To avoid jeopardizing achievement of the goals and targets of the Malabo Declaration overall, we need to prevent a global food security crisis, as several analyses have already shown. The main message of these analyses is that governments should avoid panicking and keep trade channels open so that regional and international markets can work to prevent the sort of food shortages and price hikes that occurred during the food price crisis of 2007-2008 and the Ebola epidemic that hit Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone in 2014. As governments implement lockdowns to slow the spread of the virus, they also need to consider social safety nets and other policies and instruments that safeguard the food security and healthcare of the population, especially for the many people who live on a day-to-day basis. This support will help them maintain a healthy life during the lockdown and return to the labor force and agrifood system when the virus is under control and the lockdown is over.

Several actions can help African countries focus on achieving the Malabo goals and to ensure that the BRs reflect country’s progress accurately: countries must apply differential effort for meeting the milestone for different BR indicators; countries and development partners must work together to improve the availability and quality of data to help isolate and analyze the effects of COVID-19; and the AU must make the AATS methodology more robust to years affected by shocks, such as COVID-19.

Different indicators contribute differently to the overall BR score and this contribution changes over time, which imply that different efforts are needed at different times to meet the milestone for different indicators in order to stay or get on-track (Benin 2020). Comparing the progress made for the group of countries that were on-track to those that were not-on-track in the 2018 BR for example, those that were on-track need to reverse their decline for the indicators on the CAADP process (theme 1) and mutual accountability (theme 7) while maintaining their rate of progress in the other indicators. For those that were not-on-track in the 2018 BR, their main challenge is with the indicators on ending hunger (theme 3), which they must strive to improve while maintaining their rate of progress in the other indicators to get them on-track.

With COVID-19 and other external shocks, having high-quality data can help to reliably isolate and analyze their effects on the BR process and results, so that countries’ efforts in implementing the Malabo Declaration can be assessed independently of those shocks. Doing this can help avoid any disillusionment with the BR process by ensuring that the effects of COVID-19 on the BR results are not wrongly attributed to actions by countries in implementing the Malabo Declaration. In general, improvement in data quality will improve the statistical significance and reliability of estimated relationships between outcomes and policies, investments, and behavior of actors in the agrifood system. This will in turn strengthen the links between policies and investments and the BR results, so that policymakers can be confident that selecting policies and investments that lead to desirable outcomes will also lead to higher BR scores.

Reducing the impact of “outlier” years on the BR results can also instill confidence in the process. There are at least two ways to revise the AATS methodology to make it more robust to years affected by external shocks such as COVID-19 or abnormally high or low data values that are not related to the BR process and underlying policy actions and behavioral changes. The first would use the preceding year’s data and benchmark in calculating the scores. For the 2022 BR, the latest data year would be 2019 and the benchmark would be 7.16 instead of 7.66 (the benchmark for data year 2020) (see Figure 1). The downside of this approach is that it adds only one year of data, which may not be enough time to show any significant change. The second option would use all the data points from 2015 to the latest year in estimating the indicators and calculating the scores. This method is already applied for some of the indicators (e.g., 2.1i to 2.1iii on public and private investment), where the average value from 2015 to the latest data year is used. For many of other indicators that are measured as growth rates, only the 2015 and latest-year data points are used, which leaves those indicators more prone to the effect of outliers. Using all the data points from 2015 to the latest year in estimating the indicators is good for even for those years that seem normal at the global level but may be abnormal for some countries or even some indicators in the same country. The effect of these approaches on the BR results can be analyzed by redoing the calculations for the 2020 BR and examining how the recalculated results differ from what has already been released. With the first approach for example, the latest data year to use will be 2017 instead of 2018 and corresponding benchmark will be 5.33 instead of 6.66 (see Figure 1).

To conclude, the slowdown of progress by African countries in implementing the Malabo Declaration, as observed in the results of the 2020 BR, is likely to be worsened in the next 2022 BR by the COVID-19 global pandemic. This is because the data for the 2022 BR will be measured in 2020, when many of the BR indicators may see big changes for the worse as a result of the COVID-19-related economic downturn. Improving data quality to reliably isolate and analyze the effect of COVID-19 on the Malabo goals, as well as making the AATS methodology more robust to years affected by external shocks such as the COVID-19, may help avoid any disillusionment with the BR process by ensuring that the effects of COVID-19 are not wrongly attributed to countries’ actions or inactions in implementing the Malabo Declaration.

[1] Samuel Benin (s.benin@cgiar.org) is acting director of the Africa Regional Office at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Read the original blog here